Research

The global financial crisis of 2008/2009 has highlighted the pivotal role of real estate in our economy and financial system once more. The sheer size of the asset class dominates national accounts and household-level balance sheets alike, both in terms of assets and liabilities.

To be able to make better-informed decisions, academia, industry, policymakers and private households should be familiar with real estate’s risk–return profile. After all, housing accounts for nearly half of the total assets of UK households. Still, property investments are often misunderstood as being fundamentally different from more mainstream asset classes such as stocks or bonds. Simplistic advice such as “Buy land, they’re not making it anymore”, attributed to Mark Twain (there is no evidence of this provenance), is typical for a view in which real estate is exceptional: returns exceed a fair compensation for risk. Recent academic work – incorrectly – supports this view. A suggested “risk premium puzzle for housing investments” is not in line with theory and can be traced back to data shortcomings.

In my research, I strive for more realistic estimates of real estate’s risks and returns, both at the market and at the asset level. To do so, I combine theory and data, traditional econometrics and innovative machine learning techniques, dusty archives and big data sensors. I explore applied machine learning techniques to utilise high-dimensional and often “Big(ish)” data. Put differently, I use images and other data that are too complex for spreadsheets to better understand property values, fund returns, household preferences and decisions made by very human and not always rational agents.

Forthcoming and Recently Published Work

- Leow, K and T. Lindenthal (2025). “Enhancing Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) Return Forecasts via Machine Learning”

- We add to the emerging literature on machine learning empirical asset pricing by analyzing a comprehensive set of return prediction factors on REITs. We find that REIT in vestors experience significant economic gains when using machine learning forecasts. Comparing to the stock market (Gu et al. 2020), we show that REITs are more predictable than stocks, and that the superiority of non-linear machine algorithms is robust to both large and small predictor sets for REITs while stocks tend to suffer from smaller predictor sets. Risk-based signals such as secured debt emerge as the most dominant group of predictive characteristics for REITs, as opposed to price trends for stocks. For macroeconomic predictors, aggregate market variance (a risk-based factor) is the most important time series predictor for REITs, as opposed to aggregate book-to-market ratio (a fundamentals-based signal) for stocks.

All Published work

All publications can be found here.

Work in Progress

- Leow, K. and T. Lindenthal. “Machine Learning and Missing Data in Real Estate”

- NEW WORKING PAPER, FEEDBACK MUCH APPRECIATED. Real estate research tends to be plagued by missing data. We show that prediction accuracy can increase by incorporating observations with missing predictors in the case of commercial real estate. We also show that missing data may not be occurring at random, which makes it more important to incorporate all observations into a prediction model, be it complete or not. Finally, we show that when one incorporates missing data into training sets, prediction outcomes can go into opposite direction

- Clapp, J.; Nichols, J., and T. Lindenthal. “Rebuilding the City Inside and Out: Supply Kinks and Quantities”

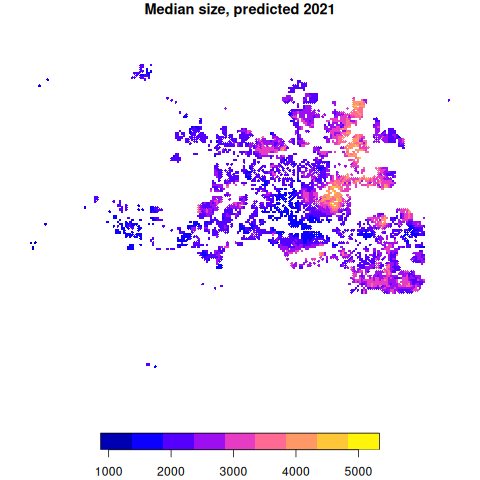

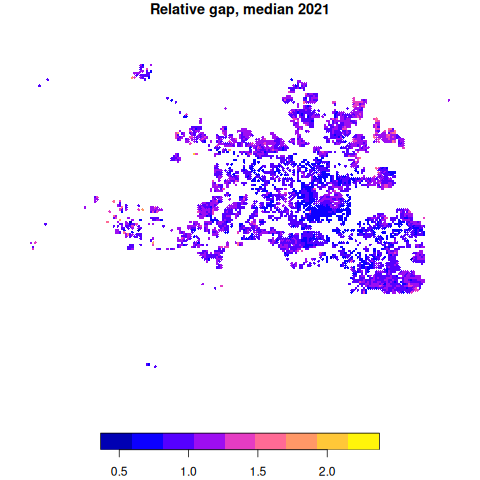

- We study intensive and extensive margins of housing supply over time and neighborhoods within a metropolitan area as a function of the existing built environment characterized. We ground our approach with an innovative durable capital model where we use inverse demand functions to generate implications for changes in housing supply instead of prices, suggesting substantial differences in dynamics across the two supply margins. This allows us to expand our empirical work to include all properties in our 14 years of Maricopa County property assessments, not just those that transact. We also innovate by estimating a machine learning model of the level of the optimal size of a residential home at all parcels, both those currently with residential properties and those without. This allows to empirically estimate the probability of a housing supply increase and the conditional size of the increase separately for each margin. Consistent with our model, the impact of the optimal home size on the extensive margin is significant, positive, and largely linear, while the impact of the gap between the optimal home size and the size of an existing home has a pronounced kink.

Predicted Int. Floor Space (sqft) |

Gap: Pred. space - current space |

- Eichholtz, P.; M. Korevaar and T. Lindenthal. “Growth and Predictability of Urban Housing Rents”

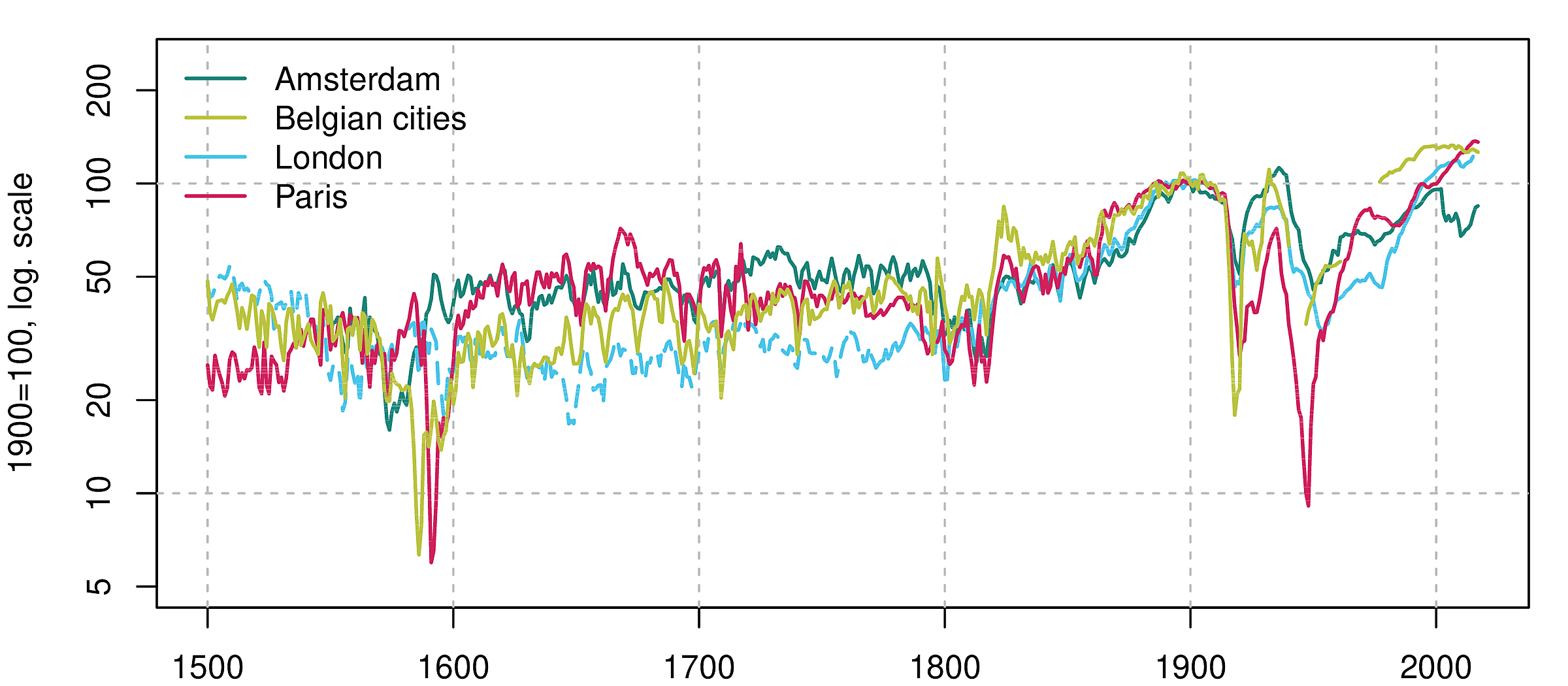

- This paper studies urban rental prices for half a millennium (1500–2020) and seven cities: Amsterdam, Antwerp, Bruges, Brussels, Ghent, London, and Paris. Based on a dataset of 436,000 rental cash flow observations, we build continuous annual indices of housing rents, which we employ to study the long-term developments in rental cash flows, as well as their predictability. We find that real rent growth has been limited, but with large differences across cities: average annual growth rates range between 0.12 percent for the Belgian cities to 0.30 percent for Paris. At the market level, we show that sluggish supply adjustment implies that past population growth negatively predicts current rental growth. At the individual asset level, we find that past excess rental growth rates are predictive of future rent revisions, and that increasing steepness of the term structure of contract rents is predictive for future rent levels.

- This paper studies urban rental prices for half a millennium (1500–2020) and seven cities: Amsterdam, Antwerp, Bruges, Brussels, Ghent, London, and Paris. Based on a dataset of 436,000 rental cash flow observations, we build continuous annual indices of housing rents, which we employ to study the long-term developments in rental cash flows, as well as their predictability. We find that real rent growth has been limited, but with large differences across cities: average annual growth rates range between 0.12 percent for the Belgian cities to 0.30 percent for Paris. At the market level, we show that sluggish supply adjustment implies that past population growth negatively predicts current rental growth. At the individual asset level, we find that past excess rental growth rates are predictive of future rent revisions, and that increasing steepness of the term structure of contract rents is predictive for future rent levels.

- Eichholtz, P.; M. Korevaar and T. Lindenthal. “The Housing Affordability Revolution”

- This paper provides the first long-term overview of developments in urban housing affordability, quality and inequality, focusing on seven European cities from 1500 to the present. Based on the rental indices developed by EKL (2022), we create new indices of housing quality and inequality, and relate these to changes in wages and population. Before 1900, markets were unregulated and rent prices and wages rose in tandem when cities grew while housing quality and inequality increased. We document a housing affordability revolution between the 1910s and the 1970s when housing affordability and quality improved dramatically while housing consumption inequality declined. We show that part of the short-term affordability improvement in this period was attributable to rent controls and housing supply expansions. Most of the surge in housing expenditure that did occur over time is due to increasing housing quality rather than rising rent.

- T. Lindenthal and C. Schmidt. “The Odd One Out: Asset Uniqueness and Price Precision”

- Lindenthal T. and P. Eichholtz. “That’s What We Paid for It: The Spell of the Home Purchase Price through the Centuries”